Here's how Republicans or Democrats can win control of Congress in the next election.

Republicans could introduce and support the tax increases the Democrats have demanded, with no strings or spending cuts attached.

or

Democrats could introduce and support the spending cuts Republicans have demanded, with no strings or tax increases attached.

Whichever party does this then says to the electorate: "We have demonstrated that we can govern. Now put us in control and we will solve the nation's problems."

Thursday, November 24, 2011

Why the Supercommittee Failed

As we discussed in an earlier post, the incentives were simply not present to cause the supercommittee to make any hard choices or come up with any innovative solutions, whether on a "Grand Bargain," the $1.2 trillion sequestration or even a smaller step towards fiscal sanity.

But some other, parallel reasons existed for its failure and they're cogently explained in this post today by Ron Elving, the senior Washington editor for NPR News. The full post is at www.npr.org/people/1930203/ron-elving.

But some other, parallel reasons existed for its failure and they're cogently explained in this post today by Ron Elving, the senior Washington editor for NPR News. The full post is at www.npr.org/people/1930203/ron-elving.

. . . a democratically elected government is not a business. There is no business strategy, no business model and only limited agreement on what "the business" ought to be doing. Instead, the component parts of the business function independently and often at odds with each other. The analogy, in short, does not work.

So the dozen people on the deficit panel reverted in the end to the self-protective behaviors that characterize politicians under pressure. Realizing their various constituencies would be better off in the short run without a compromise requiring sacrifice of everyone, the two sides elected to punt. The plans they submitted to each other were more about conflict than compromise.

That is exactly the same dynamic that has kept Congress from doing anything productive about the deficit since the year 2000 . . .

The problem at base is that the country has been told too many pleasant lies and too few uncomfortable truths by both its major political parties. It is not possible to go on having all the government we're used to (including entitlements and half the world's total defense spending) and blithely send the bill to somebody else (either in the present or the future). It can't continue and it won't.. . .

Both parties act as though they can blame the other, striving to please constituencies that insist they do so. Yet, few achievements in American history have been so bipartisan as the national debt.

It took two centuries to reach $1 trillion and became a major campaign issue for Republican Ronald Reagan in 1980. In the three decades that followed, the debt rose from $1 trillion to $12 trillion. During that period, Republicans were in the White House two-thirds of the time. Both chambers of Congress had Democratic majorities for 12 years, Republican majorities for 10 years and 6 months and divided control for 7 years and 6 months.

Monday, November 21, 2011

The Supercommittee's Failure and the President's Responsibility

On this Monday, essentially all of the political and economic commentators in the land appear to have concluded that the supercommittee has failed in it's assigned task of finding agreement as to some combination of $1.2 trillion in increased revenues and/or spending cuts. In fact, some of our earlier posts had contemplated precisely this outcome.

As has also been noted in earlier posts, the incentives needed to convince the parties to reach a deal were simply not present here, so the result is not surprising.

That said, and putting to one side the forthcoming political theater in which each side will blame the other (you may want to help your blood pressure by tuning out for the next 72 hours!), a few comments regarding the President's role, or non-role, in this process bear noting.

In real life in politics, serious budget deals get done when Presidents get directly involved, and use the leverage of their office to cajole, threaten and put pressure (especially of public ridicule) on both sides. As another writer noted today, "A few phone calls and tepid public statements do not count. It is the executive, not the legislature, that gives the budget process energy and direction."

In fact, that's exactly what happened in the budget/tax deals which took place under Reagan, Bush 1 and Clinton.

I'm told that the Vice President's deficit talks earlier this year found about $400 billion in relatively easily identified budget cuts, while the Republicans recently put forward a relatively modest $300 billion in additional revenues. Clearly, the ingredients were there for at least a mini-deal (say, $700 billion?), if not the hoped-for $1.2 trillion in revenues and/or cuts.

My experience, as a trained mediator and with 40+ years as a business attorney, is that when parties are more than half way to a deal, it's not unusual for them to be pushed all the way to a complete deal.

But it does take a push, and usually from someone other than the parties themselves.

But what happened was, once again, that the President absented himself from the rough work necessary to bang heads and seize the moment.

Is it conflict aversion or something else?

I cannot but help be reminded of his earlier failures to push for fiscal balance when the Bush tax cuts were extended (which gave the Republicans what they wanted and caused the President to lose valuable leverage in the Summer debt ceiling debacle), which was in turn resolved by "kicking the can down the road" to the super committee. Recall that in that case, what the President did achieve was to put off further debt ceiling discussions until after Election Day in 2013.

Note also the decision in Afghanistan to begin withdrawals in advance of the election, perhaps also motivated by political considerations rather than military advice. I may be self-delusional, but I do see a pattern here.

It seems clear that when the nation needs strong leadership from the President,at least in the fiscal arena, he has been found wanting. Even from a non-partisan standpoint, and I hear this from my Democratic friends as well, we do not have a strong President.

Perhaps the President's campaign slogan in 2008 will be revived, but this time for use by the other side: "Change we can believe in."

As has also been noted in earlier posts, the incentives needed to convince the parties to reach a deal were simply not present here, so the result is not surprising.

That said, and putting to one side the forthcoming political theater in which each side will blame the other (you may want to help your blood pressure by tuning out for the next 72 hours!), a few comments regarding the President's role, or non-role, in this process bear noting.

In real life in politics, serious budget deals get done when Presidents get directly involved, and use the leverage of their office to cajole, threaten and put pressure (especially of public ridicule) on both sides. As another writer noted today, "A few phone calls and tepid public statements do not count. It is the executive, not the legislature, that gives the budget process energy and direction."

In fact, that's exactly what happened in the budget/tax deals which took place under Reagan, Bush 1 and Clinton.

I'm told that the Vice President's deficit talks earlier this year found about $400 billion in relatively easily identified budget cuts, while the Republicans recently put forward a relatively modest $300 billion in additional revenues. Clearly, the ingredients were there for at least a mini-deal (say, $700 billion?), if not the hoped-for $1.2 trillion in revenues and/or cuts.

My experience, as a trained mediator and with 40+ years as a business attorney, is that when parties are more than half way to a deal, it's not unusual for them to be pushed all the way to a complete deal.

But it does take a push, and usually from someone other than the parties themselves.

But what happened was, once again, that the President absented himself from the rough work necessary to bang heads and seize the moment.

Is it conflict aversion or something else?

I cannot but help be reminded of his earlier failures to push for fiscal balance when the Bush tax cuts were extended (which gave the Republicans what they wanted and caused the President to lose valuable leverage in the Summer debt ceiling debacle), which was in turn resolved by "kicking the can down the road" to the super committee. Recall that in that case, what the President did achieve was to put off further debt ceiling discussions until after Election Day in 2013.

Note also the decision in Afghanistan to begin withdrawals in advance of the election, perhaps also motivated by political considerations rather than military advice. I may be self-delusional, but I do see a pattern here.

It seems clear that when the nation needs strong leadership from the President,at least in the fiscal arena, he has been found wanting. Even from a non-partisan standpoint, and I hear this from my Democratic friends as well, we do not have a strong President.

Perhaps the President's campaign slogan in 2008 will be revived, but this time for use by the other side: "Change we can believe in."

Friday, November 18, 2011

Why the Supercommittee May Not Matter

As a follow-up to some of our recent posts, an article in today's Washington Post (www.washingtonpost.com/politics/supercommittee-appears-unlikely-to-reach-agreement/2011/11/17/gIQAjk43VN_story.html?hpid=z3) makes it clear that it's reasonably likely that the fiscal "supercommittee" will not be able to reach agreement on spending cuts and, in fact, may not have much incentive to do so.

As Senator Max Baucus commented, "We’re at a time in American history where everybody's afraid — afraid of losing their job — to move toward the center. A deadline is insufficient."

For those with some memory on the subject, they'll recall that an impending government shutdown forced the first budget deal, in April of this year. Then, in August, the possibility of a default was necessary for the compromise that resulted in the establishment of the supercommittee.

As the Post's article comments, "even normally optimistic aides close to the process conceded that it may be time to pull the plug."

So, let's assume that the supercommittee fails to reach agreement, as seems likely. What happens next?

Well, here's a likely scenario:

1. Each side blames the other.

2. No cuts take place until 2013.

3. The Democrats go into the 2012 election claiming that the Republicans want to dismantle Social Security and the safety net, while the Republicans claim that the Democrats will raise taxes on the middle class and spend the nation into bankruptcy.

4. The 2012 election may be one of the few truly important elections in our history, at least from a fiscal standpoint.

Once again, we're reminded that the first law of economics is scarcity: people's demands for goods and services (including from government) is endless, as compared to the available supply.

And the first law of politics is to ignore the first law of economics.

As Senator Max Baucus commented, "We’re at a time in American history where everybody's afraid — afraid of losing their job — to move toward the center. A deadline is insufficient."

For those with some memory on the subject, they'll recall that an impending government shutdown forced the first budget deal, in April of this year. Then, in August, the possibility of a default was necessary for the compromise that resulted in the establishment of the supercommittee.

As the Post's article comments, "even normally optimistic aides close to the process conceded that it may be time to pull the plug."

So, let's assume that the supercommittee fails to reach agreement, as seems likely. What happens next?

Well, here's a likely scenario:

1. Each side blames the other.

2. No cuts take place until 2013.

3. The Democrats go into the 2012 election claiming that the Republicans want to dismantle Social Security and the safety net, while the Republicans claim that the Democrats will raise taxes on the middle class and spend the nation into bankruptcy.

4. The 2012 election may be one of the few truly important elections in our history, at least from a fiscal standpoint.

Once again, we're reminded that the first law of economics is scarcity: people's demands for goods and services (including from government) is endless, as compared to the available supply.

And the first law of politics is to ignore the first law of economics.

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Defense Spending and Some Perspective

When it comes to possible budget cuts, one area that receives attention is the Defense Dept. budget.

To put the current defense budget in perspective, let's look at a few charts, courtesy of The Foreign Policy Initiative (see www.foreignpolicyi.org/content/defense-spending-super-committee-and-price-greatness)

First, over the period since WW 2, the driver in increased federal spending has been entitlements, not defense.

Second, defense spending as a percentage of all federal spending is near an historic low.

Third, defense spending has already been subject to a series of reductions under the current Administration, with long-term cuts amounting to about $850 billion. In a very real sense, the Defense Department may be able to say that it "already gave at the office."

May there still be some "fat" to be cut?

Maybe.

Has the defense budget already taken significant cuts?

Absolutely.

To put the current defense budget in perspective, let's look at a few charts, courtesy of The Foreign Policy Initiative (see www.foreignpolicyi.org/content/defense-spending-super-committee-and-price-greatness)

First, over the period since WW 2, the driver in increased federal spending has been entitlements, not defense.

Second, defense spending as a percentage of all federal spending is near an historic low.

Third, defense spending has already been subject to a series of reductions under the current Administration, with long-term cuts amounting to about $850 billion. In a very real sense, the Defense Department may be able to say that it "already gave at the office."

May there still be some "fat" to be cut?

Maybe.

Has the defense budget already taken significant cuts?

Absolutely.

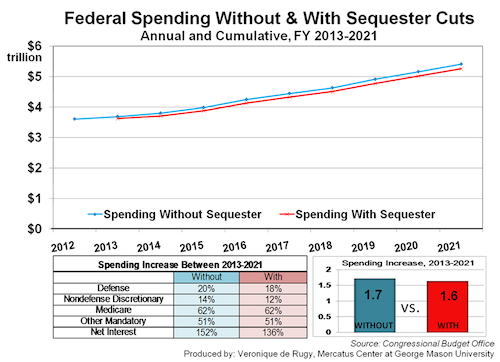

Sequestration and A Reality Check – Part Two

Let’s assume, perhaps out of an excess of pessimism, that the Supercommittee does not agree on $1.2 trillion in savings, the mandated cuts are triggered and no legislation passes avoiding such cuts.

How much money would actually be saved by the sequestration of the otherwise planned spending?

The answer, disappointingly, is: Not much.

As a study (see http://mercatus.org/publication/federal-spending-without-sequester-cuts) by Veronique de Rugy at George Mason University shows, using Congressional Budget Office numbers, the “sequestration” of planned spending would result in total additional spending by 2011 of $1.6 trillion; without sequestration, the additional spending would be $1.7 trillion.

So, the total effect of sequestration would be a reduction in spending of less than 6% and far less than the President’s Fiscal Commission recommended.

Examine her graph below, and if you can see the difference between the two lines, your eyes are better than mine:

The takeaway? If the Supercommittee doesn't reach agreement, and the planned amounts are sequestered, we’re still headed off a financial cliff, albeit at a trot, rather than a gallop.

If they do reach agreement, but only to the extent of the otherwise sequestered amount, and fail to "think bigger," the same result applies.

It makes one wonder a bit as to what the fuss is about in the media re whether or not the sequestration trigger gets pulled.

It makes one wonder a bit as to what the fuss is about in the media re whether or not the sequestration trigger gets pulled.

Sequestration and A Reality Check – Part One

In this last week before the supposed deadline for the Supercommittee to resolve the issue of possible budget cuts, perhaps it’s a good time to do a reality check.

It’s a common belief, and I’d suggest an incorrect one, that if the Supercommittee fails to reach an agreement on $1.2 trillion in budget cuts over the next 10 years, there will be mandatory cuts in both the defense and non-defense budgets.

[Note that even if the Supercommittee does not each agreement, any “triggered” budget cuts will not take effect until 2013.]

Well, yes – on one level that’s what the deal was, as reached by the President and the Republicans this Summer, and as enacted by Congress (and signed by the President) at that time.

However what Congress does can be undone, subject only to a Presidential veto, which can (in turn) be undone by Congress.

Thus, if no agreement is reached, Congress could simply amend or repeal its earlier law mandating any “triggered” budget cuts.

Speculating, it seems unlikely that the President would veto any such acts of Congress, particularly if they were supported by many Democratic members of the House and Senate.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)